Microbiologists are always interested in knowing how many bacteria are present in a sample. You could say they’re obsessed with establishing how many invisible little bugs are growing in whatever system they happen to be studying. My job is to know how many nasties are in milk, its derivatives — whey powder, cheese, skim milk, et cetera — and the equipment used to process it. Numbers of bacteria per millilitre or gram or square centimetre is not a particularly easy thing to establish, and sometimes how to do so, gives me sleepless nights. But that’s for another blog.

Microbiologists are always interested in knowing how many bacteria are present in a sample. You could say they’re obsessed with establishing how many invisible little bugs are growing in whatever system they happen to be studying. My job is to know how many nasties are in milk, its derivatives — whey powder, cheese, skim milk, et cetera — and the equipment used to process it. Numbers of bacteria per millilitre or gram or square centimetre is not a particularly easy thing to establish, and sometimes how to do so, gives me sleepless nights. But that’s for another blog.

When microbiologists speak about levels of bacteria in food or water or soil we do not refer to X number of bacteria per gram: we use colony forming units (CFUs). The CFU has been used since the very start of analytical microbiology, and when you learn of how the vast majority of quantitative assays are carried out by microbiologists as well as the nature of microbial growth you will understand just how rational it is to use CFUs. From the late nineteenth century, when agar-based solid media began to be used for growing bugs, and with the Petri dish becoming established as the format of choice for holding the media, microbiologists have observed that bacteria tend to form colonies on such nutritive solid surfaces.

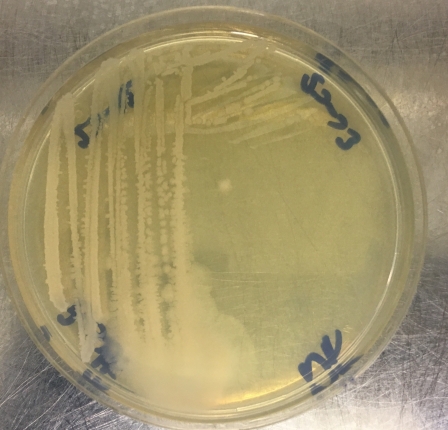

A colony is simply the visible glob made up of billions of bacteria and which arises from the rapid, ceaseless exponential growth of a single founding cell (or cluster of cells — more anon). If you put any* live microbial cell on a solid growth medium which contains the correct balance of salts, proteins, energy sources and vitamins and incubate at the bug’s optimal temperature and with the right mix of gases (some bugs don’t like oxygen — the strict anaerobes) you will have a visible colony in a day or two. Now, some bugs are incredibly fussy, and it has taken the best part of a century to work out what media suit their growth (species of Mycobacterium are notoriously hard to grow), but for the majority of the bugs of interest to your average food microbiologist there are media which will have your lads forming colonies in double quick time.

The discovery of colonial growth was a huge step forward for microbiology. Prior to this, the only way to count bugs was by eye. “But they’re microscopic!” I hear you say. Indeed and they are! Prior to the days of the Petri dish, you put your sample on a special gridded slide, stained the bugs as best you could, hunkered down over your microscope and got counting until your eyeball dried up! Not pleasant work. And not very accurate. We humans are subjective and tend to make mistakes. Was that a rod or a coccus or just a salt crystal? It is far, far easier to take a sample, say a swab from the surface of a meat counter, get the bacteria into suspension in water or a solution such as Ringer’s which has salts that will help keep the bugs alive, and put that suspension to grow on a dish. You come back the next day and count the colonies and you know how many bugs were in the sample. Simple, isn’t it?

Yes, but it comes with a proviso. While bacteria are single-celled organisms, not all bacteria exist as single cells. Some bugs grow in chains, others in clusters (Staphylococcus aureus is characterised by “bunch of grape” clusters under microscopic examination), and others exist as pairs or triplets. And then there are biofilms: huge, sometimes macroscopic amalgamations of bacteria trapped in their extracellular secretions. So, when you get your sample of suspended bacteria and plate it out on a Petri dish you are generally not dealing of a uniform suspension of single cells. And when these lads land on the surface of the agar and begin to grow it can be anything from one cell to dozens that give rise to your colony. Hence, to be strictly correct, each colony that has grown up is not evidence of the outgrowth of a single cell — it is evidence of the outgrowth of a colony forming unit. And the number that your microbiologist comes up with is an estimate, because they can never know how many bugs make up a colony forming unit.

*Not really any. Molecular studies have shown that perhaps less than 1% of microbial species have been ever grown on artificial media. It is really only the bacteria that are capable of growth on artificial media that us microbiologists know much about. But luckily, it is the ones of interest to us medically, environmentally and biotechnologically that have tended to be amenable to our trying to grow them. The rest of the microbial world are something resembling dark matter: we know they are there, but not very much else.