I love my bit of country rock, my wee daily dose of Americana. And ol’ Gram Parsons would be in the mix there, depending on the mood. But today I’m going to write about another Gram. A surname Gram, if you get my drift. And a man far removed from the world of the Byrds, Flying Burrito Brothers and cowboy boots.

I love my bit of country rock, my wee daily dose of Americana. And ol’ Gram Parsons would be in the mix there, depending on the mood. But today I’m going to write about another Gram. A surname Gram, if you get my drift. And a man far removed from the world of the Byrds, Flying Burrito Brothers and cowboy boots.

Hans Christian Joachim Gram was a Danish microbiologist who could be described as the father of bacterial strain identification. For it was he who gave us the simple but effective staining method that has split the eubacterial kingdom right down the middle. After staining, a bacterium is either Gram-positive or -negative*.

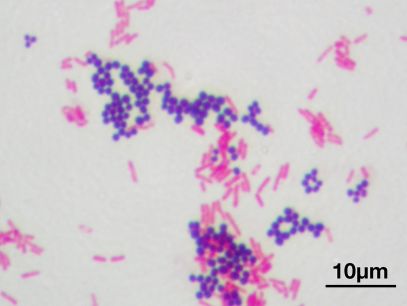

In 1884, Gram was working in the morgue of a Berlin hospital and wished to devise a stain that would colour up the bugs from sections of lung tissue and allow them to be discriminated from the background human cells. After some trial and error and a few modifications, we got what is now called the Gram stain. The stain works on the basis of dyes that react with the bacterial cell wall, which is composed of peptidoglycan. One group of bacteria have a thick layer of peptidoglycan, while another has a thin layer that is surrounded on the outside by a thick (and sometimes gooey) lipid membrane. The first stain applied during Gram staining, crystal violet, stains both types of cells purple. The next additive, iodine, is a mordant#, which in the case of the thick-walled cells fixes the crystal violet’s purple colour, but is occluded from the second group of cells by the lipid layer. Alcohol is then applied to the cells. This washes out the loosely held dye from the thin-walled cells, decolourising them, while having little effect on the thick-walled cells, which remain purple. A second colour (either safranin or fuschin, both red) is then added to the cells. This addition does not affect the thick-walled cells, which remain purple, while the colourless, thin-walled cells are now stained red. And so we have in a simple staining method two broad groups of cells distinguished on the basis of cell envelope morphology. Combined with other morphological features that can be seen under a reasonably high-powered microscope, the Gram stain yields a deal of information about the mystery bugs under investigation.

After isolating a bug, Gram staining is the first port of call for a bug hunter. A bug being Gram-positive or -negative allows us microbiologists to rule our mystery organism out of belonging to about 50% of the eubacterial kingdom. Whatsmore, in taking a gawk at our isolate under the microscope to check for Gram status we also get to cop a look at cell morphology. Is the critter a rod? Or a coccus (round)? Is it boat-shaped? Sausage-shaped? Are there spores? Do the cells occur in bunches of grapes? Or in chains? Do the cells exist as tetrads? Et cetera. Us bug hunters then follow a protocol to narrow down the possibilities of what our isolate might be. We test for the presence of enzymes such as catalase and oxidase. We test for the bug’s ability to metabolise a host of carbon sources. And finally, if we want to be really precise, we sequence the blighter’s DNA and compare it to a database of previously identified isolates.

Thus, the modern microbiologist is using a mixture of techniques, some of which date from the nineteenth century, and some which were invented last year. And even in this day and age of next-generation sequencing and CRISPR and aptamers all that, it’s still not time for Gram to sling his guitar!

*There’s a couple of “buts” and “howevers”, however. Some strains are Gram-variable. Depending on culture age or physiological state, they can be positive or negative. But these are outliers in a very successful and venerable classification system.

#A mordant is a substance that combines with a dye or stain and thereby fixes it in a material.